Number rotation has been a go-to tactic for callers trying to stay ahead of spam flags. The strategy goes something like this: rotate numbers throughout the day, making 50 calls from one line and then switching to another. If a number gets flagged, replace it with a “fresh” one.

It’s a tactic that’s been passed around the industry for so long, it’s become accepted wisdom.

The problem is: it no longer works.

That tactic, aggressively adopted by scammers, forced carriers to adapt their algorithms to detect and penalize the behavior. And they have.

Yet few are talking about it. And good businesses keep doing it. That’s part of why over 4 in 5 businesses report losing revenue to spam flags.

It’s time to dispel this myth once and for all.

To do that, we need to look at how carriers identify number rotation, why it backfires so spectacularly (often flagging entire groups of numbers at once), and what actually works instead.

I’ve spent my career working at the intersection of outbound calling, carrier networks, and the analytics engines that decide which calls get through and which don’t. As CEO of PhoneBurner and ARMOR®, I deal daily with the real-world consequences of how those systems evaluate calls at scale.

Prior to this, I spent time inside the call analytics ecosystem, including work with Hiya—one of the companies directly involved in how calls are labeled, scored, and filtered.

The team behind ARMOR® brings even greater depth of experience. Collectively, we’ve worked alongside multiple carriers and analytics providers that shape today’s spam-flag ecosystem, including close collaboration with organizations like AT&T and First Orion.

That vantage point gives us an understanding of how flags are created, propagated, and enforced that few teams have. And it’s that perspective this post is grounded in.

Before we get into how carriers identify number rotation, it helps to examine the assumption that keeps callers coming back to this strategy.

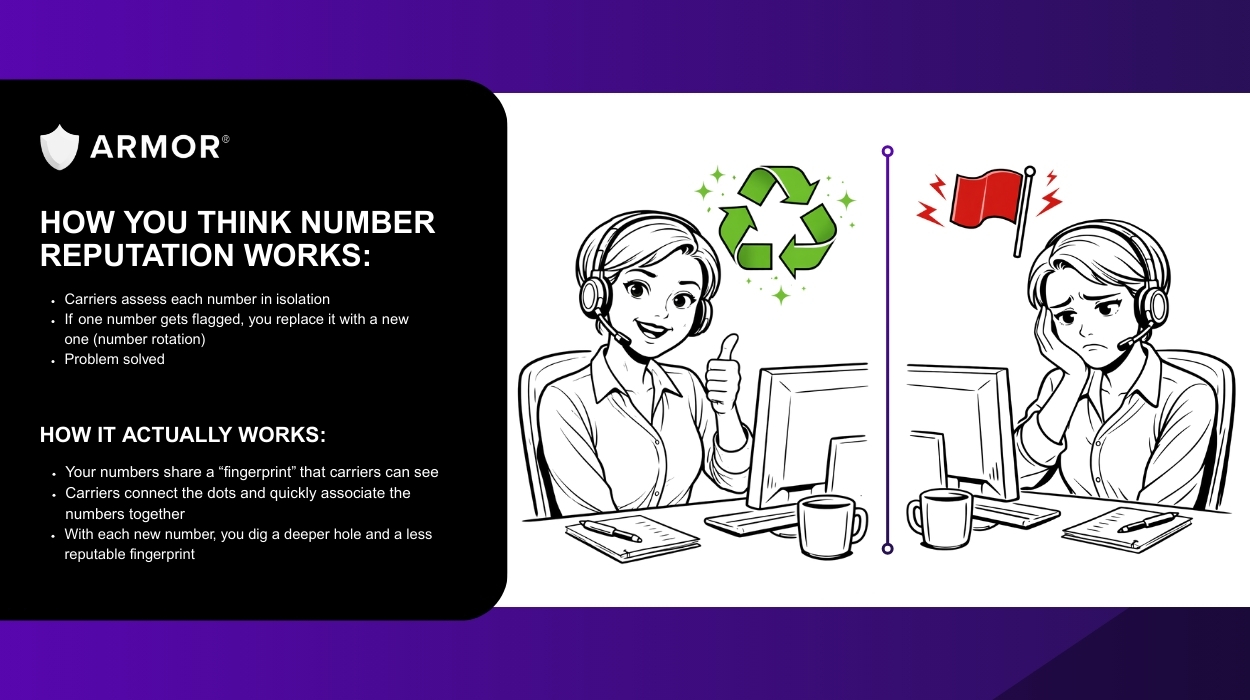

Number rotation is built on a flawed assumption: that carriers evaluate each phone number in isolation. If one number runs into trouble, replacing it should reset the clock. New number, clean slate.

Implicit in that logic is another belief: that risk can be diluted. If the behavior generating negative signals is spread across enough numbers, no single number does “enough” to draw attention. Volume gets distributed. Exposure gets reduced.

At one point, that assumption held up.

But as Hiya has reported, number rotation became so prevalent that it now appears in more than half of illegal robocall campaigns. In over a quarter of those campaigns, every single call is made from a newly rotated number.

Let that sink in for a moment.

For many numbers, the entire lifespan is a single call.

When rotation reaches that level of scale, carriers are forced to confront the reality that judging numbers one by one is no longer effective.

“Number rotation is built on a flawed assumption: that carriers evaluate each phone number in isolation.” — Chris Sorensen

Today, carriers don’t just ask whether a number looks risky. They look for patterns that tie different numbers together. And they’re very good at it.

Because when you step back and analyze calls this way, one thing becomes clear very quickly:

Different numbers often have far more in common than callers realize.

Bad actors don’t rely on a single phone number. And legitimate businesses don’t either. So modern carrier systems have to answer a broader question:

Are these calls related?

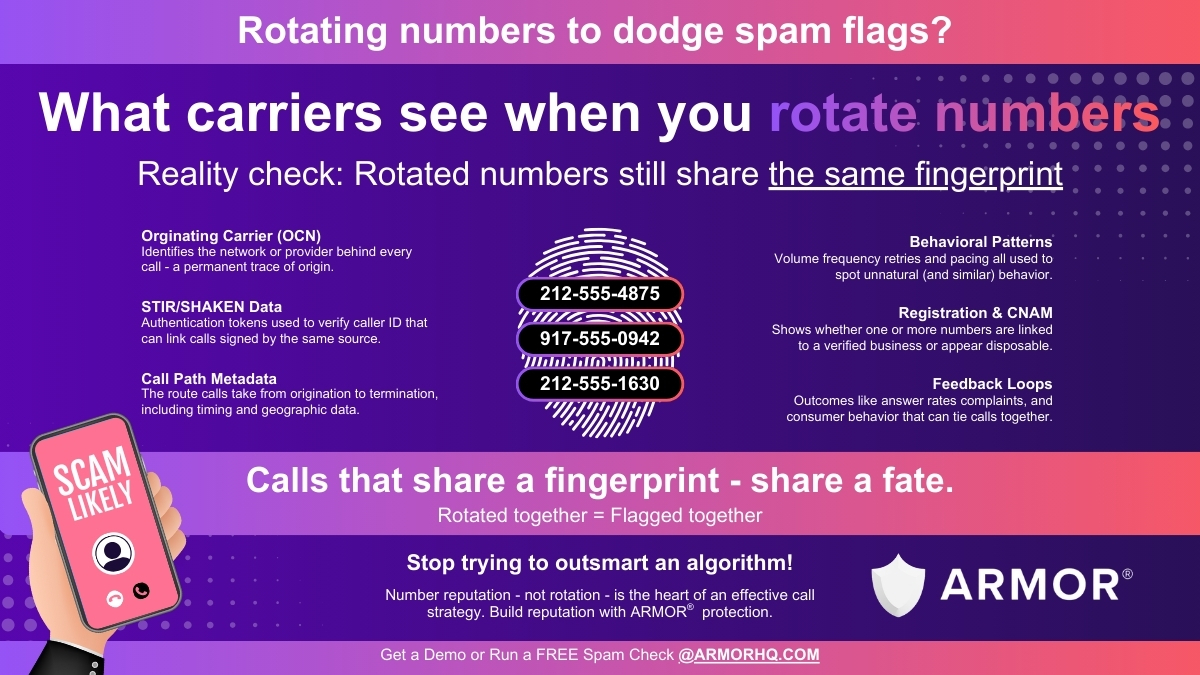

Every call carries a set of signals that describe where it originated, how it was delivered, and what happened once it reached the network. Taken together, those signals form something far more durable than a caller ID: a fingerprint.

That fingerprint doesn’t change because the number does.

Think of it like a bank robber wearing different masks. The disguise may change from one robbery to the next, but the underlying patterns, and, ultimately, the fingerprint, remain the same. Investigators don’t need the same face to connect the crimes.

Carrier algorithms work the same way, because call identity runs far deeper than a Caller ID.

Let’s look at some of the most important signals that contribute to that shared fingerprint.

Related: 27 Factors That Can Drive Up Your Spam Flag Risk

Carrier algorithms analyze a unique set of signals that help identify how, where, and from whom a call originates. Together, these signals form a fingerprint that connects your calls back to you—no matter how many times or numbers you rotate.

Rotated numbers still share:

Every call originates from a specific carrier or network. That origin doesn’t change when you rotate numbers, making it a consistent signal carriers use to link related calls.

STIR/SHAKEN goes a level deeper, providing identity verification that incorporates both number- and carrier-level signals. Calls are signed and authenticated, leaving breadcrumbs that persist even when the caller ID changes.

Carriers see how calls move through the network, including routing paths, timing, geography, and handoffs. When different numbers share call path metadata, it’s a thread algorithms can use to associate them.

Carriers track behavioral signals such as volume, pacing, retries, calling windows, and call duration. These underlying behaviors rarely change, which means rotation simply reproduces the same patterns across multiple numbers.

Numbers tied to the same business typically share registration details and CNAM (Caller ID Name) information, making their common identity evident. Skipping registration doesn’t eliminate attribution—it increases scrutiny, while every other fingerprint signal still applies.

Answer rates, complaints, blocking behavior, and consumer engagement don’t reset with a new caller ID. When outcomes cluster, carriers treat the calls that produced them as part of the same group.

Bottom line?

Carriers connect the dots.

Once calls are evaluated through the lens of shared fingerprints, the failure of number rotation becomes clear.

From a carrier’s perspective, rotating numbers doesn’t disperse activity; it concentrates it.

Multiple caller IDs exhibiting the same underlying signals form a clear cluster of related behavior that’s easier to evaluate than a single number. The more numbers you rotate through, the more data you generate, and the faster the shared fingerprint becomes undeniable.

At that point, unless engagement signals are consistently positive, rotation stops looking like normal business behavior and starts looking like evasion—an attempt to dodge trust-building rather than address the underlying reputation issue. That’s why carriers invest heavily in systems designed to detect and shut it down.

This is where rotation turns from ineffective to counterproductive.

Because when calls share a fingerprint, they share a fate.

Entire groups of numbers can be flagged together. And once that happens, new numbers tied to the same fingerprint tend to be flagged faster than the ones that came before.

From the carrier’s perspective, patterns like these are interpreted as:

Taken together, rotation doesn’t protect caller identity; it actively undermines it.

Rotation is evasive. So what’s the answer?

Once you understand how carrier systems evaluate calls, one thing becomes obvious: trying to outsmart the algorithm is a losing game.

These systems aren’t static. They adapt constantly, and they’re trained on massive amounts of real-world data. Any tactic designed to “stay one step ahead” eventually gets folded into the model.

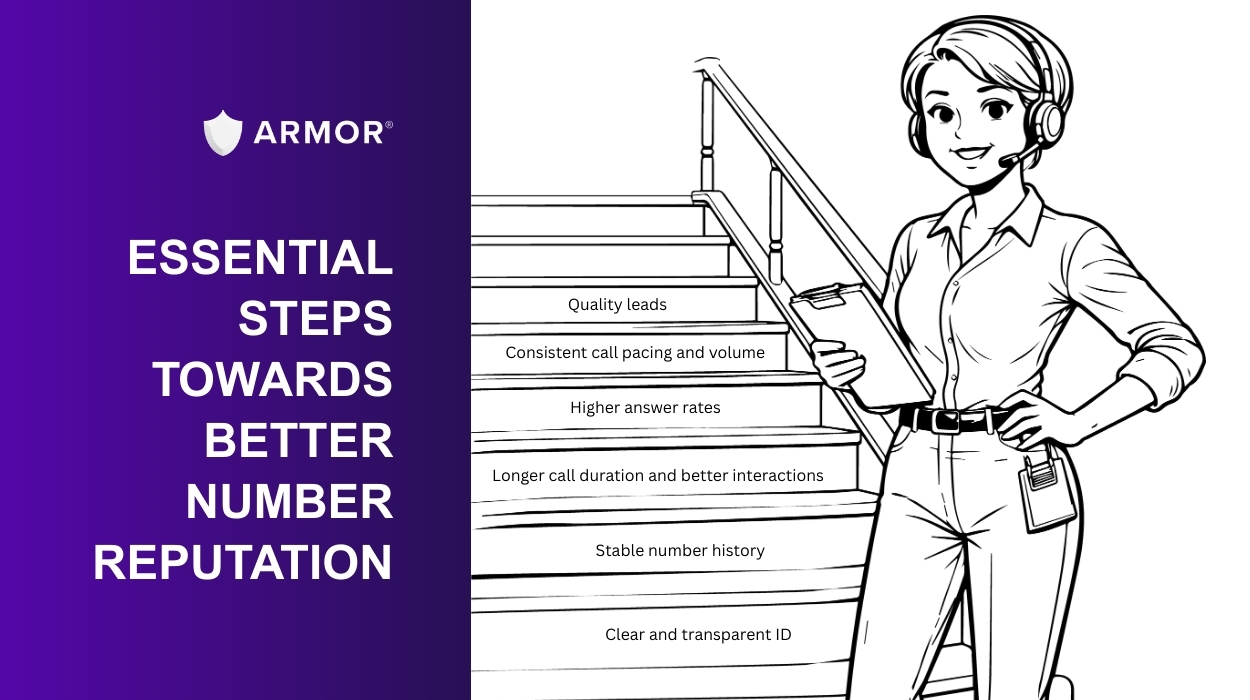

What holds up over time is simple: quality.

Carriers reward the same things customers do: calls that are wanted, relevant, and timely. That shows up across a range of signals, from how numbers are used to how people respond when they’re called. And those signals can be measured.

In practice, that means shifting away from tactics meant to mask problems and toward fundamentals that actually improve outcomes:

None of this is about gaming the system. It’s about aligning with how carriers and their subscribers want and expect to be contacted.

That’s the lens to apply when thinking about how multiple numbers should be used, and it’s where the conversation around healthy number distribution starts to look very different from rotation as a tactic.

Like most rules, there are exceptions.

Using, and even “rotating,” multiple numbers in a limited sense can be part of a healthy calling strategy when the underlying fundamentals are right. In this context, rotation means spreading call volume across multiple numbers to support consistency, not to escape consequences.

This kind of rotation looks very different from the evasive behavior carriers are trained to detect. It’s not about resetting reputation, hiding activity, or cycling through disposable numbers. It’s about managing scale responsibly while keeping behavior stable and predictable.

In practice, it usually looks like this:

In this model, multiple numbers support healthy calling patterns and engagement instead of working against them. The numbers are owned, registered, consistently used, and maintained like the long-term business assets they are.

Number rotation fails because it’s built on the idea that you can outmaneuver the algorithm.

You can’t.

Carrier systems are designed to reward trust, consistency, and positive engagement over time. The teams that perform best aren’t trying to stay one step ahead of those systems. They’re adopting a quality-first approach instead.

That means treating reputation as an asset: something you earn, protect, and strengthen over time, rather than something you try to reset.

The sooner you start building that foundation, the stronger your calling program becomes.

The ARMOR® service supports that approach through proactive number protection, ongoing monitoring, and data-backed remediation. Powerful call analytics give teams visibility into emerging issues, opportunities for optimization, and the ability to fine-tune strategy for long-term performance.

If persistent flags and unanswered calls are holding you back, we can help.

Book a no-obligation demo today.